The history of combat sports, such as grappling, wrestling, and boxing, seem to reach back even before the beginning of recorded history. Egyptian depictions of wrestlers at Beni Hasan, shown below, date back to at least 2000 BC. Other sources, such as the the ancient literary work the Epic of Gilgamesh, provide even earlier testimonies of the existence of combat sports. Pitting one man’s strength and skill against that of another has been an apparent form of conflict resolution for millennia. From wild wrestling in ancient Mesopotamia to structured grappling in medieval Ireland, the history of combat sports seems to spread across nearly every continent throughout history.

Mesopotamian Region

References to combat sports in literature, even fictional, serve as excellent historical anchors in the history of combat sports. The Epic of Giglamesh (c. 2100 BC), one of mankind’s earliest surviving pieces of literature, tells the tale of the godlike king of Uruk after whom the poem is titled. One of the highlights of this story lies at the end of its first chapter, when Enkidu, a wild man made by the gods to match Gilgamesh in strength and power, challenges the king. The story relates that the two of them grapple fiercely, smashing doorposts and shaking the walls, until Gilgamesh finally throws his opponent. This tells us the people of ancient Mesopotamia did grapple to some degree, with at least one form’s goal involving overturning the opponent (though use of pins and holds or lack thereof is unknown). Within Mesopotamian culture, Gilgamesh appears to have been held as a godlike example of masculinity and power, indicating that grappling may have been a popular sport during that period, whether for entertainment or conflict resolution.

Mediterranean Region

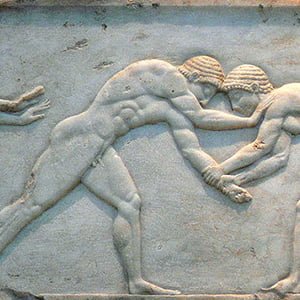

There are many more extant sources regarding the history of combat sports in ancient Greece than in ancient Mesopotamia, providing a much clearer picture of what they were like. Though the Olympic Games initially only featured running contests, combat sports were eventually added in the following years; wrestling (called palé) in 708 BC, boxing (called pygmachia) in 688 BC, and pankration (a violent sport with few rules) in 648 BC.

Wrestling held a sizable place in Greek culture, and was featured in the Panhellenic games both independently and as part of the pentathlon. To begin a match, the two opponents would lean into each other with their foreheads touching, standing in the middle of a wrestling pit called a skamma. They were given no time limit for the fight. While kicks and punches were not permitted (unlike aforementioned pankration and, of course, boxing), most chokes and holds on the upper body were allowed, as well as sweeps to the legs. The goal was to throw the opponent, landing them on their back and/or shoulders, in order to score a fall. Submissions and holds deemed by the judges to be inescapable were also counted as a fall. As there appears to have been no break between rounds, the felled opponent would have had to immediately right themselves and continue fighting after a scored fall. The first one to score three falls won the match.

Contrasting common opinion of wrestlers in modern times, successful athletes were regarded as somewhat intellectually gifted. Good technique and cunningness were regarded more highly than brute strength alone. As there were no weight classes, smaller contestants had to rely on skill over strength to overcome their larger piers, though the latter nevertheless dominated the sport.

Middle East

Much like the Mesopotamian region, combat sports seem to have been immensely popular in the ancient Middle East. A form of grappling called malla-yuddha (which translated from Sanskrit means “wrestling combat”) was practiced in India as early as 500 BC, and is still in practice in parts of South India today, making it one of the longest-running entries in the history of combat sports. This combat sport involved grappling, striking, certain holds, and sometimes even biting. It was separated into four forms, each progressively more violent, with its final form consisting of ferocious, full contact striking and sometimes limb-breaking holds. In contrast to wrestling in ancient Greek, malla-yuddha placed special emphasis on the strength of the participants rather than their technique. For example, the goal of its second form, one of the most common still practiced today, was to lift the opponent off the ground for a full three seconds.

*Malla-yuddha was likely practiced much earlier than 500 BC, but its earliest literary reference comes form the Hindu epic Ramayana, which dates around that period.

Far East

Though Asia plays a less central role in the history of combat sports, it has hosted many isolated forms of throughout its history. As early as the 3rd millennium BC, Chinese marital artists engaged in a sport called jiao di (lit. horn butting) to some degree, though records of it are scant. In one of several possible variations of the sport, the two opponents would don horned headgear and attempt to butt the other off a raised platform called the lei tai.

Throughout the ages the sport adopted throwing techniques, bringing it closer in line with what we would call wrestling or grappling. By the end of the 2nd millennium BC it had given way to a new sport called jiao li, which historical records seem to indicate was a form of wrestling with some marital-arts-flavored striking and blocking. This was quite a popular spectator sport during the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BC). Competitors would wrestle on the lei tai, on which the winner of each round would remain to face the next challenger until there were no more left, king-of-the-ring style. When no more fighters were left, the final man standing would be named champion. The sport was practiced among soldiers in China throughout the centuries, and even today several styles are still practiced under the name shuaijiao (or shuai jiao, translated “to throw to the ground through wrestling with legs”).

European Region

The history of combat sports surges in Medieval Europe, where a wide variety of such sports were enjoyed among many regions and classes. In the 16th century, all social classes engaged in a wide variety of regional forms of wrestling and grappling. Germans widely participated in geselliges ringen, a relatively safe form of grappling in which joint locks and other dangerous maneuvers were prohibited, with the ultimate goal of a throw or submission.

In the same period the Irish participated in a sport called coraíocht (which may even have ties back to the Tailteann Games as early as 632 BC), better known today as “Collar-and-Elbow,” in which the goal was to maintain a pin of both shoulders and hips for five full seconds. To begin, the opponents would face each other, grab the other’s collar with their right hand and the elbow with their left hand. From this standing position they would circle each other while trying to gain the proper leverage and positioning to take down the opponent via a throw or a sweep. Once on the ground, they would employ various grappling techniques and holds in an attempt to pin the opponent. Participants of coraíocht valued a balance of speed and strength to be able to quickly move into leverageable positions for swift takedowns. In America’s early history, this style was heavily influential and very widely practiced among all classes, making it perhaps one of the most widespread styles of wrestling in the modern history of combat sports.

Anonymous, & George, A. (2003). The epic of Gilgamesh. Penguin Classics.Miller, C. (2004, May).

Young, D. C. (2004). A brief history of the Olympic games. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

Miller, S. G. (2006). Ancient Greek athletics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Newby, Z. (2006). Athletics in the ancient world. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press.

Phillips, D. J., & Pritchard, D. (2011). Sport and festival in the ancient Greek world. Swansea: The Classical Press of Wales.

London: J. Murray.Swaddling, J. (2015). The ancient Olympic games. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Arvanitis, J. (2003). Pankration: The traditional Greek combat sport and modern mixed martial art. Boulder, CO: Paladin Press.

Liddell, H. G., Scott, R. (2007). Liddell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon. Simon Wallenburg Press.

Poliakoff, M. (1995). Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, violence, and culture. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Alter, J. S. (1992). The wrestler’s body: Identity and ideology in north India. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Draeger, D. F., & Smith, R. W. (1985). Comprehensive Asian fighting arts. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Chennault, C., Knapp, K., Berkowitz, A., & Dien, A. (2015). Early Chinese texts: A bibliographical guide. Institute of East Asian Studies.

Wu, D., & Murphy, P. D. (1994). Handbook of Chinese popular culture. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Meyer, J. (2014). The art of combat: A German martial arts treatise of 1570. London: Greenhill.

Desch-Obi, M. T. (2008). Fighting for honor: The history of African martial art traditions in the Atlantic world. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Redmond, P. R. (2014). The Irish and the making of American sport, 1835-1920. McFarland.

Hurley, J. W. (2011). Shillelagh: The Irish fighting stick. Pipersville, PA: Caravat Press.

Submission Fighting and the Rules of Ancient Greek Wrestling [PDF]. Judo Information Site.Smith, W., Wayte, W., & Marindin, G. E. (1890). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

Peterson, I. V. (2003). Design and rhetoric in a Sanskrit court epic: The Kirātārjunīya of Bhāravi. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Auboyer, J. (2002). Daily life in ancient India: From 200 BC to 700 AD. London: Phoenix.Tong, Z., & Cartmell, T. (2005). The method of Chinese wrestling. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Wushu History. (1995). Translated section from Wushu International Judge Teaching Materials – edition 1995. International Wushu Federation. Retrieved from http://www.eagleclaw.gr/en/historyw.htm

O’Brien, J. (2007). Nei jia quan: Internal martial arts. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books/Blue Snake Books.Sports and games in ancient China. (1986). Beijing, China: New World Press.Welle, R. (1993). “–und wisse das alle höbischeit kompt von deme ringen”: Der Ringkampf als adelige Kunst im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Pfaffenweiler: Centaurus-Verlagsgesellschaft.

Wilson, C. M. (1959). The magnificent scufflers; revealing the great days when America wrestled the world. Brattleboro, VT: Stephen Greene Press.