The history of rugby ties in closely with both the history of soccer and American football, as all three sports owe their origins to medieval European mob football games. In the Middle Ages, these chaotic sports were played all throughout Europe, with different regional traditions giving each sport a unique twist. These sports slowly faded out as fewer branches of more structured football games started to emerge in Europe during the 19th century. It was during this period that the game of rugby football began to reach the peak of its development, poised to become one of the most popular football sports worldwide.

Modern materials addressing the history of rugby and other football sports often link them with ancient sports, especially within Greco-Roman culture. While there is no evidence to suggest such games have any historical link with rugby, their similarities are discussed under Mediterranean Region immediately below. Information on the history of rugby football in earnest begins under European Region further down.

Mediterranean Region

Greece

The ancient Greek game episkyros, played in Greece around the 5th century BC, is one such game often referred to as a predecessor of modern football. Accounts of this game are sparse, making it difficult to ascertain its rules. However, some of its basic mechanics have been pieced together, and they bear a level of similarity to rugby. Teams of 12 to 14 players would attempt to move a ball past the opponent’s back line, though the methods to do so are not well elaborated. It seems one such method was to move past the back line while holding the ball, much like tries in rugby. Episkyros also seems to have included interceptions, passes, tackles, and other rugby-esque features.

Despite these similarities, episkyros has no known connections with the development of football sports in Europe. As such, despite the coincidental similarities between episkyros and rugby, it does not directly contribute to the history of rugby.

Rome

The case is similar with the Roman game harpastum, largely due to the fact that this sport was a Roman adaptation of episkyros. As such, the two sports share many characteristics. However, accounts of harpastum suggest the sport was even more dissimilar to rugby than its predecessor.

Its rules are difficult to determine in their entirety, but it seems harpastum was somewhat of an inversion of episkyros. Instead of trying to move a ball past the opponent, the goal of each team seems to have been to keep the ball within their own zone, as defined by lines on the field, while keeping the opponent from possession. Despite these differences, the game still featured some aforementioned elements of modern rugby – interceptions, passes, tackles, and more – though these are coincidental. As such, like episkyros, harpastum does not directly contribute to the history of rugby either.

European Region

Medieval Europe is where the history of rugby – as well as football in all its modern forms – truly began. European history is filled with mob football sports in seemingly endless variation, though only a handful of these sports were widely practiced. Even fewer of these Middle Age games have had their rules accurately preserved to the extent that we can study them in some detail. Most of them share more characteristics with rugby than with soccer. The four primary games with the most surviving historical information are French la soule, Welsh cnapan, Irish caid, and Italian calcio fiorentino. These sports are discussed in more detail below, ordered by increasing similarity to rugby.

These four sports are not necessarily ordered chronologically below. With regard to their historical timeframe, the first three sports have fuzzy origins that mix together. The earliest reference to such games lies in the 9th century AD, though it’s possible some of them were played for some time before that. The fourth sport, Italian calcio fiorentino, seems to have entered the scene several centuries after the others, peaking during the Renaissance era. These details are all elaborated in their respectively linked articles.

France

The French game la soule was perhaps the most variable of these medieval mob football sports, as it seems to have featured more adaptations than its cousins.* In all its variations, two or more teams, each representing their respective parishes, would attempt to move a ball to a predetermined point – typically their village’s church porch. With each team consisting of 10 to 100 players, playing fields spanning across miles of variable terrain, and matches lasting all daylight hours, this was a sport of truly massive scale.

Despite the difference in scale, la soule did bear some similarities to modern rugby. To handle the ball, payers typically ran it, kicked it, and passed it to other players.* In addition, the game was very physical, involving tackles and the like. It serves as an early entry in both the history of rugby and the history of football as a whole.

*In two variations, la soule au pied and shouler a la crosse, players were restricted soccer-style and hockey-style ball handling, respectively. In all other variations, the ball handling seems to have been similar to that of rugby.

Wales

The Welsh game of cnapan, featuring fewer variations than la soule, narrows in a little more closely to the modern rugby formula. Its basic mechanics were the same; two or more teams vied to transport the ball to their own parish. Players were not restricted with regard to handling the ball, and thus likely took a rugby-style approach of running and throwing it – though this ball was wooden and lubricated, and thus easy to lose control over. Since this ball was wooden, it is doubtful that it was kicked much, if at all.

Cnapan did differ from other medieval mob football sports with regard to scale. There was no limit to the number of men on a team, and player count sometimes reached into the thousands; the 16th century historian George Owen of Henllys reported that matches often included over 2,000 men. To make matters more chaotic, those who could afford to do so played atop horseback. The near absence of rules allowed for perhaps the most violent and chaotic sport in the history of football sports.

Ireland

The Irish game of caid, drawing back in scale, was one of the earliest sports to roughly foreshadow the style, size, and mechanics of rugby. While one variation closely matched other mob football sports with massive teams, expansive fields, and long matches, another variation was much smaller. This version was played in a set field, which would have allowed for far fewer players due to limited space. At each end of the field was a triangular goal formed by boughs of two trees, through which each team tried to pass the ball. As the caid ball was usually made of an inflated animal bladder covered with leather, players could comfortably drop kick it through the goal in addition to running and throwing it, foreshadowing the development of drop goals.

All of these elements seem to describe a game quite similar to rugby. Though the concept of scoring a try seems to be absent, the players could technically run the ball through the boughs – though kicking or throwing it likely would have been much more common. In addition, this appears to be one of the earliest examples of goal posts, though obviously grounded and connected at the top. It was later in the history of rugby that these goal posts took a different shape and were elevated from the ground, discussed under England further down.

Italy

Moving away from the chaos of mob football games, the high-class, Italian Renaissance era sport calcio fiorentino pulled everything back to the field. This rugby-esque sport was played in a sand court around 130 ft. by 260 ft., typically in a public square with seating for spectators. The most famous of these was the court in Piazza Santa Croce, located in Florence. The game was played almost exclusively by nobility and was closely associated with the royal Medici family.

Based on accounts of the game, the play style of calcio fiorentino seems to have been very similar to that of rugby, though with larger numbers of players. Each team had 27 players, meaning this average sized court was packed with 54 men. They were allowed to physically fight each other, so tackling and grappling were all part of the sport, though pikemen on the sidelines would intervene when things got too heated.

Ball handling was not restricted, so players could carry the ball, kick it, throw it, and pass it however they liked. The goal of each team was to pass the ball over the opposing team’s back barrier.* This seems to be another predecessor to the drop goal in rugby; all of these elements start to align fairly well with the archetype of the modern sport. Looking at the history of rugby from chaotic mob matches to this fielded game of strategy and skill, the beginnings of this rugged sport start to come into focus.

*The modern rendition of calcio fiorentino places a net behind the barrier that the scoring team is not to overshoot, under threat of penalty. This limits the height of a scoring throw or kick. Accounts of the original sport don’t make it clear whether there was such a height limit for scoring, though depictions of the game don’t seem to indicate there was.

England & Development of Rugby

All of these wildly disparate football sports began to come to a head in the 19th century. In England, some of these variations began to form what would become arguably three of the biggest sports in the modern world: soccer, American football, and rugby.

In the 1830s, the Rugby School in Rugby, Warwickshire, England played a variation of football where players were allowed to pick up and run with the ball. Early records of the game don’t clarify whether this was a novel development of the school or a relic from a local history of mob football. As the school was founded in 1567, during which different styles of mob football were still widely played, it is quite likely the latter was the case.

A few decades later, Ebenezer Cobb Morley (1831–1924), a lawyer and an avid football fan, got the ball rolling on the development of soccer. In 1863 he wrote to a London newspaper suggesting that an administrative organization be established to unify the sport of football. Up until that point, the sport was played with countless variations among different schools throughout England. Morley’s efforts led to the swift formation of the Football Association and the eventual adoption of their set of rules, which came to be known as association football, or soccer.

Meanwhile, rugby football resisted this trend. Ball carrying and “hacking,” a term for shin kicking, were two points of contention during the codification of association football in 1863, as up until that point they were allowed in some variations of the game. The Football Association chose to prohibit these moves, further distinguishing its game from the rough sport slowly spreading out from Rugby, Warwickshire. In January of 1871, representatives of 21 different clubs and schools which played rugby football met to unify the sport, much like the Football Association did 8 years prior. These men formed the Rugby Football Union, which published its official set of rugby rules 6 months later.

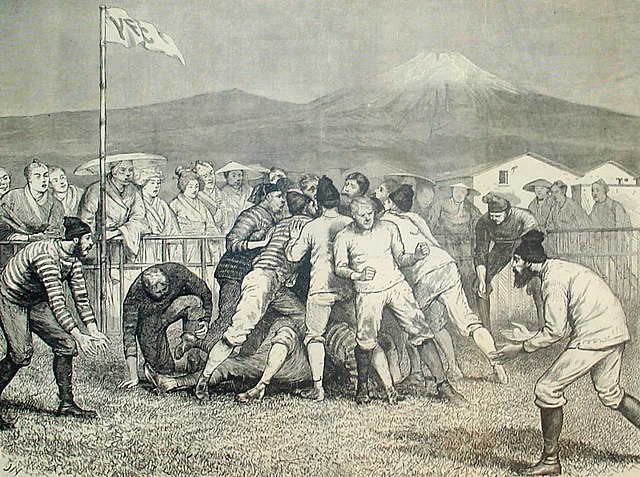

By the late 19th century, rugby had spread to the far corners of the world. Not only had America picked up the sport, but other countries such New Zealand and Japan had formed teams as well. This blossoming sport even influenced the development of American football during the late 19th and early 20th century. Soccer and rugby were very distinct from each other by this point, no longer considered variations of the same sport. Over a relatively short period of time, rugby football had elbowed its way past initial dissension and unified its disparate branches, earning its place as a worldwide phenomenon.

Further Reading

There are several other historical sports that are often referenced in modern materials discussing the history of rugby football. Because of the lack of much similarity between these games and rugby, in addition to their lack of influence on rugby’s development, they are excluded from this article. For further reading, these sports include Japanese kemari, Chinese cuju, Australian Aboriginal marn grook and to a lesser extent woggabaliri, and the Mesoamerican ball game.

Harris, H. A. (1972). Sport in Greece and Rome. Cornell University Press.

Crowther, N. B. (2007). Sport in ancient times. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Rowley, C. (2015). The shared origins of football, rugby, and soccer. Rowman & Littlefield.

Parrish, C., & Nauright, J. (2014). Soccer around the world: A cultural guide to the world’s favorite sport. ABC-CLIO.

Guttmann, A. (2007). Sports: The first five millennia. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Merkel, U. (2015). Identity discourses and communities in international events, festivals and spectacles. Springer.

Galen, C., & Singer, P. N. (1997). Galen: Selected works. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marples, M. (1954). A history of football. London: Secker & Warburg.

Williams, G. (2007). Sport: A literary anthology. Summersdale LTD – ROW.

Magoun, F. P. (1929). Football in medieval England and in Middle-English literature.

Bradby, H. C. (1900). Rugby, Handbooks to the great public schools. G. Bell and Sons.