Hawaiian ancient surfing is the term given to surf sports enjoyed among natives of the Hawaiian Islands before the modern reinvention and global spread of the sport. Historically, ancient surfing was a very central part of ancient Hawaiian culture, likely practiced for well over a thousand years before European contact in the 18th century. Once considered a quirky, isolated pastime, surfing has since spread far and wide, bringing with it tastes of Hawaiian culture to every corner of the globe.

Throughout nearly the entire history of Hawaii, surfing has been a cultural tradition practiced among all classes. From commoners to kings, nearly everyone enjoyed the sport and the festivities associated with it. Though surfing, by its nature, is typically thought of as noncompetitive, races on the ancient Hawaiin swells were commonplace, and they were often subject to wagers. In fact, wagering was nearly inseparable from the sport, which attributed to surfing’s suppression under missionary influence in the 19th century.

Even religion tied into this form of ancient surfing; in an attempt to call forth big swells from the sea, Hawaiian priests would whip the waters with vines and surfers would pray fervently at shrines. Similarly, ancient Hawaiian surf boards were crafted with special religious rituals intended to bless the craft – especially so for boards meant for royalty. The religious air surrounding the sport aligned with the attention and loyalty it received from its practitioners. The famous Hawaiian historian Kepelino (c. 1830–1878) recorded in his Kepelino’s Traditions of Hawaii, “Expert surfers going upland to farm, if part way up perhaps they look back and see the rollers combing the beach, will leave their work … they will pick up the board and go. All thought of work is at an end, only that of sport is left. The wife may go hungry, the children, the whole family, but the head of the house does not care. He is all for sport, that is his food.”

History

Prehistory

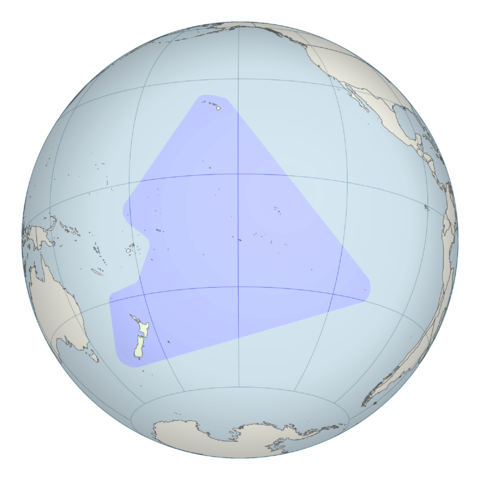

Evidence of the practice of various forms of ancient surfing can be found among many Polynesian settlements, often simply children’s games, catching waves with any piece of wood or brush, though sometimes more sportive. This near-universal presence of ancient surfing sports among the islands within the Polynesian Triangle (defined by Hawaii, New Zealand, and Easter Island) suggests that the sport predates settlement of the Hawaiian islands. While it is a possibility that these separate Polynesian settlements developed ancient surfing sports independently, it is fairly unlikely. As such, since Hawaii was settled in the 4th century at the earliest, this would suggest that the history of surfing extends back beyond 1,700 years at the minimum. As Hawaii had no written language prior to European contact in the 18th century, much of ancient surfing history is unrecorded. What we know of the sport is ascertained from its 18th- and 19th-century records.

Recorded History

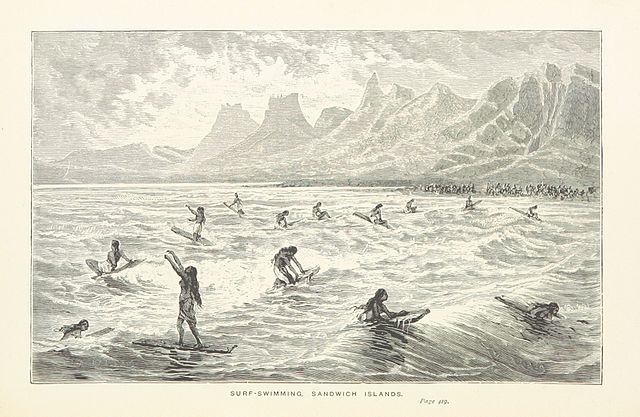

The earliest written accounts of surfing come from the Western pens of the British explorer Captain James Cook and his crew in the late 18th century. The sport was very much looked down upon for this entire period, and as European influence over the natives increased, traditional Hawaiian culture began to unravel. Early 19th-century missionaries discouraged many traditional sports for their danger, paganism, and gambling (perhaps most notable in boxing, mokomoko), and surfing received the brunt of these efforts. In addition to the gambling and pagan rituals surrounding the sport, the Hawaiian beachfront was incredibly sexualized. Typically, athletes would strip before surfing, in part to attract a romantic partner – flirting was almost as central to the sport as gambling was. As missionaries naturally discouraged this kind of environment, the sport nearly died out in the mid 19th century.

Despite the fallback, surfing began to rise in popularity again in the early 20th century, and with a continued rise in traditional Hawaiian culture, this ancient sport was roaring again within a few decades. As surfing spread outward from Hawaii, continental American audiences took to the sport very quickly, and a following picked up in California, resulting in the first generation of surfing beach bums.

How to Play

As ancient Hawaiian surfboards didn’t have stabilizing fins, the focus of ancient surfing throughout its prehistorical period was not as much about maneuvering on the wave. These surfboards were much more difficult to ride than modern surfboards, so merely staying upright on a swell took considerable skill. A particularly adept surfer would switch positions while on the wave, moving from the standard prone position among kneeling, sitting, and standing.

Racing competitions were fairly commonplace in ancient Hawaii. After bets had been placed, the two competitors would swim out into the water together to find a suitable wave. Back toward the shore, a buoy would serve as the goal. When the competitors agreed on an approaching wave, they would paddle furiously toward the shore and prepare to catch it. Contrasting the typical nudity of ancient surfers, these racers wore bright red loincloths, likely to be more easily seen by spectators on the shore and to determine with more certainty who reached the goal first.

Equipment

Surfboards, traditionally called papa he’e nalu (literally “wave-sliding board,” similar to the lava-sedding papa holua), were very special pieces of property in ancient Hawaiian culture. Oftentimes, an individual’s surfboard was their most prized possession, and those that were well kept were somewhat of a status symbol. These boards were typically made of koa, breadfruit, or wiliwili wood, and were crafted in one of three forms, each with a different purpose. These three types of surfboards were alaia, olo, and paipo.

Alaia

The alaia was the standard board used in ancient surfing. It was a thin board, carved between 2 inches and a brittle half-inch thick, around 6 or 7 feet long, and typically weighing around 50 to 100 pounds. It was carved with a round nose, a squared-off tail, and, as stated above, no fin. Unlike the olo board, detailed below, alaia were sometimes crafted in an expedited process, skipping some of the finish and most of the religious rituals intended to bless the board. For the average native Hawaiian, the alaia was the board of choice.

Olo

The olo was a much more special board, crafted exclusively for royalty. It was an incredibly large board; typically 15 to 20 feet long and 2 feet wide, with a curved top and bottom that could bring the middle of the board up to 8 inches in thickness. It received a glossy black stain and was treated with coconut oil in between uses, giving it an immaculate, shiny exterior. As the board was massive and typically weighed around 150 pounds, it was not very maneuverable in the water. The olo might be more comparable to a surfing canoe, wherein the goal is not to carve through the wave, but simply to maintain an upright position and prevent the craft from becoming an unwieldy projectile.

The olo underwent a special crafting process that took more time than for the other boards. First, after finding a good tree out of which to craft the board, a red kumu fish would be placed at its base. After cutting the tree down, a hole would be carved into the stump or root system, into which the fish would be placed as sacrificial compensation for the tree. After the trunk was shaped down in the halau (canoe shed), the emerging board would be smoothed and sanded with pumice and coral. As mentioned above, the board was typically stained with a charcoal-based gloss and sealed with coconut oil. Throughout this whole process, prayers and other religious ceremonies were used to bless the board, with one final prayer offered before its first launch into the sea.

Paipo

The paipo was the smallest and most inexpensive surfboard in ancient Hawaii. This type was most often used by children, though a few adults owned them as well. They were shaped similarly to the alaia, with a round nose and squared tail, but were much smaller; about 16 inches wide, an inch and a half thick, and a length between 3 feet (for children) and 6 feet (for adults). It was mostly ridden prone, but the rider could kneel or stand as well. Though a prayer may be offered before its first launch, the paipo had little ceremonious preparation, and was typically crafted as quickly as possible.

Warshaw, M. (2010). The history of surfing. Chronicle Books.

Finney, B. R., Houston, J. D., & Finney, B. R. (1996). Surfing: a history of the ancient Hawaiian sport. Pomegranate Artbooks.

Handy, E. S. (1965). Ancient Hawaiian civilization: a series of lectures delivered at the Kamehameha schools. Tuttle Publishing.