Hoop rolling was a Greco-Roman game, played by both youths and adults, in which a large ring was rolled, chased after, and struck by a stick or some instrument to keep it moving. While not typically considered a sport in itself, this game was physically exerting and focused on a central goal: to keep the hoop rolling as long as possible. Sometimes other challenges were incorporated, such as jumping through the hoop as it rolled or throwing spears through it. Other variations of this game have been played by many societies throughout history, but within Greco-Roman culture, hoop rolling was quite popular, and even tied in with military training in some cases.

Despite hoop rolling’s modern associations with childishness, the game was considered fairly sporty and masculine in Greco-Roman culture. Hoop rolling was even practiced as an athletic activity in the Greek gymnasium, suggesting men 18 and older engaged in the game as well. It was not featured as an event in any of the Panhellenic games, however.

Origins and History

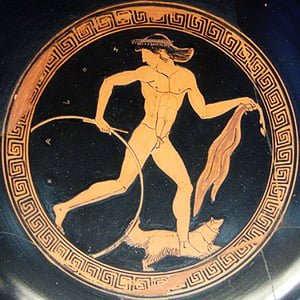

The earliest references to hoop rolling in Greco-Roman culture lie in Greek vase paintings dating from 5th century BC, as early as 450 BC. The number of paintings depicting hoop rolling suggest the sport was quite pervasive in Greek culture. Likely due to the crossover between Greek and Roman culture in the ensuing centuries, Roman society picked up the game as well, where it seems to have been nearly as pervasive.

It is doubtful that hoop rolling games from other cultures throughout history had much influence on, or were influenced by, Greco-Roman hoop rolling. In addition to a lack of evidence to suggest this, such a simple game could very easily be invented independently in different cultures, just like the development of ball games like catch or juggling.

How to Play

The basis of the game was to strike a hoop with a stick, chase after it, and continue to strike it to keep it rolling as long as possible. Beyond this, the Greeks and Romans added other objectives to make the game more interesting. In one Greek gymnastic variation, the goal was to keep jumping through the hoop while maintaining its roll. Sometimes Roman men and youth would throw spears through the hoop as it rolled as a form of both recreation and military training.

Equipment

The hoop used by the Greeks, called the krikoi in Greek, was constructed of metal and made to be just below the player’s chest height. This allowed for certain acrobatics with the hoop, such as jumping through it while rolling. As such, players would have difficulty using a hooping that was not designed for someone of their stature. To drive the hoop, the Greeks used a stick called an elater, which translates to “driver.” Based on depictions of the game, the elater typically measured 6 to 12 inches, though its construction material is unknown. It could be that the material didn’t matter, and that any item used to drive the hoop was called the elater.

The Roman hoop was called the trochus. As the Greeks sometimes used this Latin term interchangeably with the Greek word krikoi, these hoops were likely one in the same, or at least measured roughly the same in diameter. However, when Roman children played the game, they would often attach metal rings around the shaft of the hoop that would slide freely, their jingling warning passersby of the approaching hoop. The driver, called the clavis, was typically made of metal with a wood handle. Aside from these minor variations, the practice in Greek culture and Roman culture appears to have been practically identical.

König, J. (2005). Athletics and literature in the Roman empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Delaney, T., & Madigan, T. (2015). The sociology of sports: An introduction, 2nd ed. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Groos, K., & Baldwin, E. L. (2011). The play of man. Ulan Press.

Smith, W., Wayte, W., & Marindin, G. E. (1890). A dictionary of Greek and Roman antiquities. London: J. Murray.

Plummer, E. M. (1898). Athletics and games of the ancient Greeks. Cambridge, MA: Lombard & Caustic, Printers.

Pulleyn, W. (1853). The etymological compendium; or, Portfolio of origins and inventions. London: W. Tegg.