This article focuses specifically on the Greek javelin used in the Greek pentathlon.

The Greek javelin, though primarily used for war and hunting, was a recognizable icon within ancient Greek athletic culture. The javelin throw was one of the five events in the Greek pentathlon, a competition in the ancient Olympic Games, Nemean Games, and Pythian Games.

The athletic javelin, also called the akon, was a wooden pole often made of elder wood. It was about the height of a man and slightly thicker than a finger. A leather strap called an ankyle (Greek), or an amentum (Latin), was wrapped around the shaft and used to aid in throwing the spear. The tip of the javelin varied according to its function, as athletic javelins didn’t require lethal tips.

Components

The end of the Greek javelin could be pointed or blunt. If the primary goal was to pierce a target, a bronze head was attached to the end. The end would have been blunt or dipped in bronze if the spear was only for distance throwing. The athletic javelin (akon) was likely lighter than the military variation (dory), which had a broad iron point for its use as a destructive weapon

The ankyle was made of 12–18 inches of leather, wound tightly near the center of gravity on the shaft of the Greek javelin. Its use improved the stabilization, accuracy, range, and speed of the throw when compared to throwing the javelin directly from the shaft. The slight flexibility in the leather added a bit of a slingshot effect to the throw as well. When the leather unwound mid-flight, it would cause the shaft to spiral, increasing both its accuracy and distance.

Preparing the ankyle played a significant role in the success of the throw. For distance competitions, the strap would have been placed slightly behind the center of gravity, which would sacrifice some accuracy but significantly increase range.

Athletic Usage

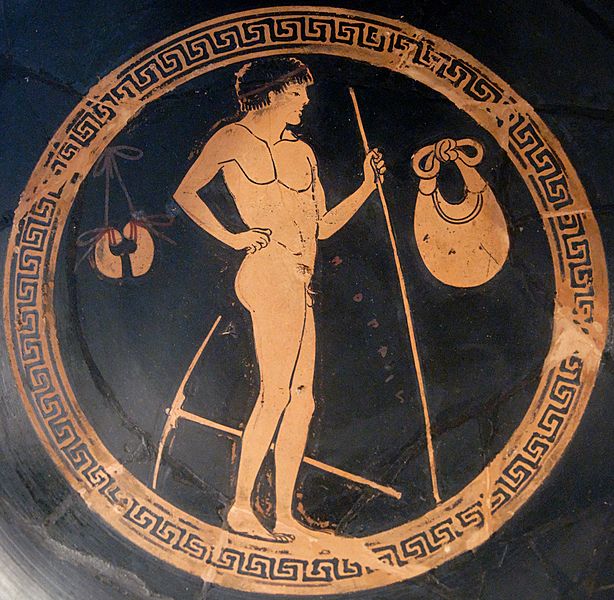

By studying paintings on ancient Greek vases, we can get an idea of what the preparation and execution of a distance throw probably looked like. Looping one end of the leather around his big toe, the athlete would roll the javelin from the other end down to his foot until only the loop was hanging loose. With his right hand, he would insert his first and middle fingers into the 3–4 inch loop and grab the shaft just above ankyle. With his left hand, he would reach forward and push back against the head of the shaft, creating tension and storing potential energy in the ankyle while preventing it from unraveling prematurely.

The athlete would then draw back his right arm and prepare to run, maintaining tension on the leather strap with his left hand. As he would begin to run, he would rotate his body slightly to the right and bring the javelin up to shoulder height. Approaching the line, he would rotate further to the right and prepare to release. As his left leg approached the line, he would bend his right leg and lean backward to adjust the angle of the throw. He would then shift his weight to the left leg and throw the javelin while swiftly rotating his body back to the left, creating extra momentum. The javelin would be launched around a 45 degree angle, and the ankyle would slip off of his fingers as it flew away.

Sweet, W. E. (1987). Sport and recreation in ancient Greece: A sourcebook with translations. New York: Oxford University Press.

Scanlon, T. F. (2014). Sport in the Greek and Roman worlds. Vol 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zarnowski, F. (2013). The pentathlon of the ancient world. McFarland.

Miller, S. G. (2006). Ancient Greek athletics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Spence, I. G. (2002). Historical dictionary of ancient Greek warfare. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

The J, Paul Getty Museum. (2000). Greek vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum: Volume 6. Getty Publications.